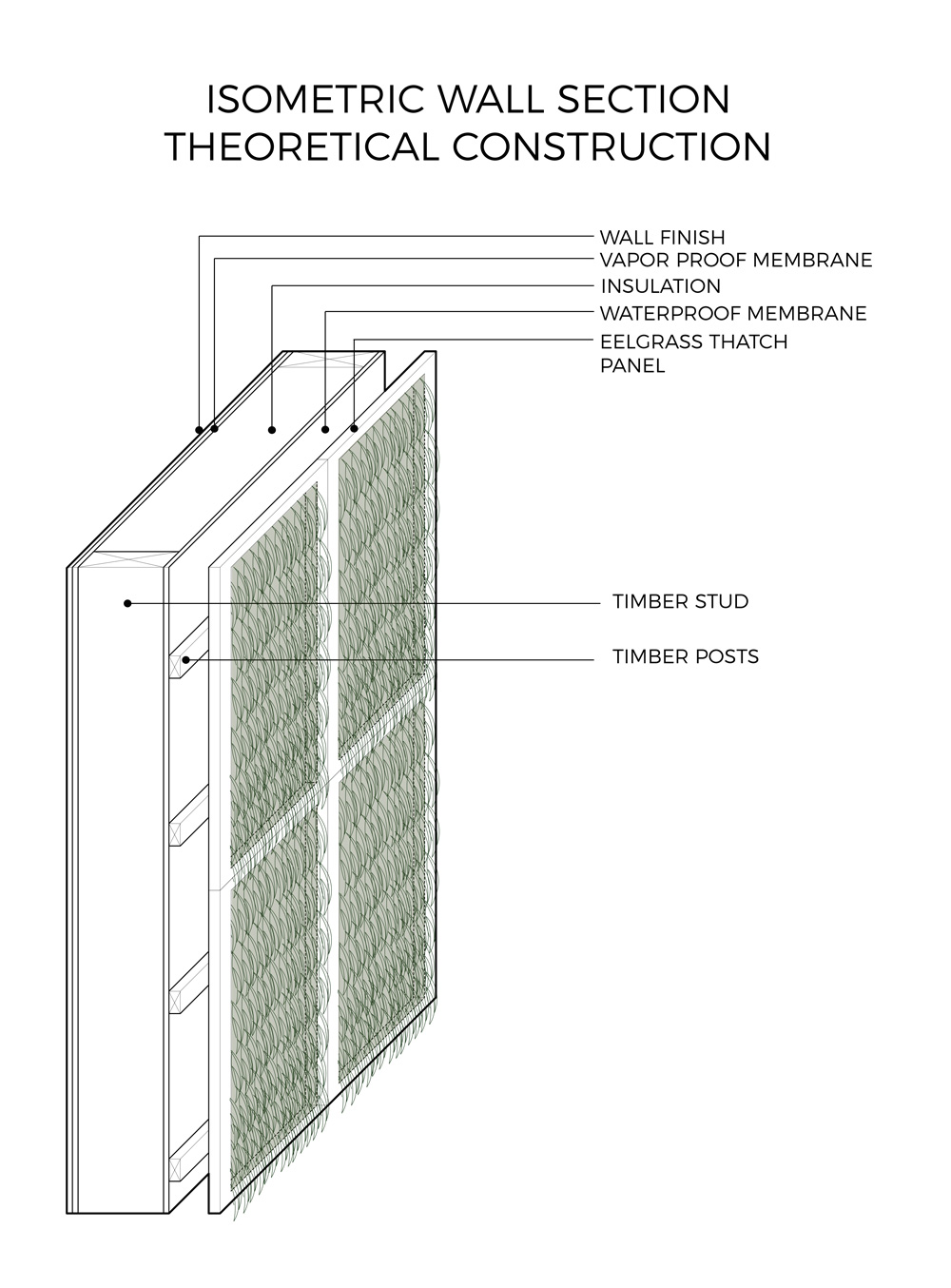

kathryn larsen has employed the centuries-old tradition of seaweed thatching, from the danish island of læsø, to develop modern seaweed thatch panels for the building industry. during her research, the denmark-based, US-born architectural technologist has found that eelgrass is a fantastic material that is naturally fireproof, rot resistant, carbon negative, and becomes waterproof entirely after about a year. it also insulates comparably with mineral wool, while plants can grow in it, giving the effect of a green roof.

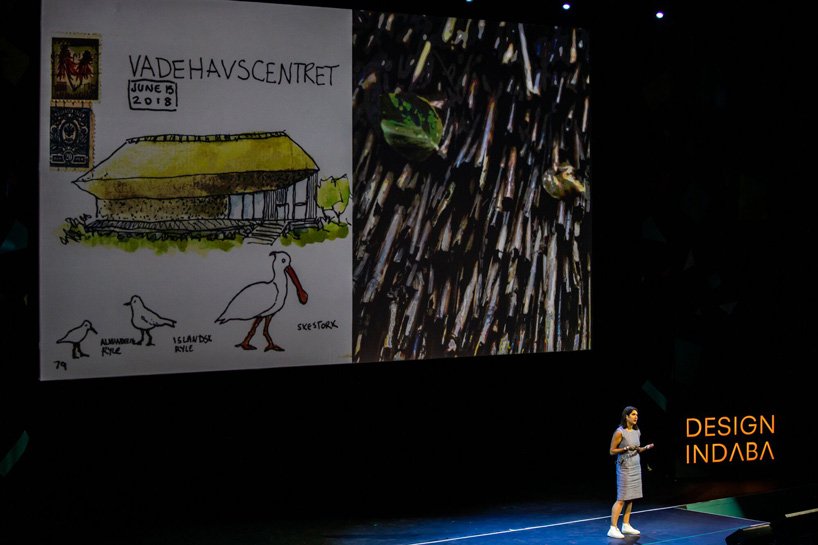

larsen, who recently presented her work and research during design indaba 2020, spoke to designboom in an interview about what first attracted her to seaweed thatching, where it originates from, and its potential applications in the building industry and beyond. all images courtesy of kathryn larsen

all images courtesy of kathryn larsen

header image and first image by anders lorentzen

kathryn larsen has used eelgrass to create prefabricated seaweed thatched panels that can be installed on roofs or façades for insulation, and, to test them, she built an installation on the roof of copenhagen school of design and technology (KEA). these panels are designed for disassembly, a principle that she also applied to the pavilion, so that all the materials involved can be reused, or recycled after the installation ends. after about eight months outside, the panels are almost entirely intact, and moss is beginning to grow on the seaweed. read the interview with kathryn larsen in full below. traditional eelgrass roof

traditional eelgrass roof

designboom (DB): can you tell a bit about how you got into the seaweed technique and what led you to it?

kathryn larsen (KL): I’m really inspired by vernacular architecture and traditional building methods. and when I came to denmark, I stumbled across these seaweed houses as I was trying to come up with a concept for a charrette. and I also stumbled across a contemporary project by vandkunsten called the modern seaweed house, but with this project, they had applied the seaweed in bags and then it’s like little pillows and attached them to this house. and I thought, what if you re-imagine this thatching technique, so that you could build with it now, in an easy way? I also had a snaggle because I had no idea how they built these homes. I had no idea how you could seaweed thatch. so until my danish got good enough, I was kind of at a standstill, figuring out, how do you actually build with seaweed? and then, by the time my thesis rolled around, my danish was good enough to figure it out and start experiments.

DB: and how did you start with the seaweed thatch re-imagined project?

KL: I studied at a school called the copenhagen school of design technology, and I got my bachelor’s in architectural technology there. I had to deliver 20 pages on anything related to the building industry. and it actually didn’t specify that you needed original research. but I had this idea in my head so strongly that I wanted to test it out.

DB: what are some modern day examples of buildings that drew your attention to this technique?

KL: definitely the waden sea visitor center, which is a thatched building by dorte mandrup architects. but I’m also really inspired by a lot of japanese architects because I feel like they go back to this sort of sense of traditional building, but then applying it in new and exciting ways. so I’m very much tied between the two countries for inspiration.

DB: the prefabricated seaweed panels can be used as insulation, right?

KL: yes, supplementary. they’re not thatched quite thick enough that they can replace installation. maybe if you were building a summer house in certain locations, you could meet the requirements. but in denmark, at least, it can only be used as supplementary for now.

DB: what is their life span? can they last for as long as normal insulation materials?

KL: actually, I think the lifespan is up to the wood more than the eelgrass because a traditional seaweed house can go up to 200 years without needing to have its roof changed. but also if you put eelgrass in a wall cavity as insulation, it could last up to 400 years. I found some sources stating it, but don’t quote me on that! but it lasts an incredibly long time, so it would have to do more with the wood being exposed to the elements.

DB: what is the scale of these panels?

KL: they’re prefabricated, so you would need to get an order for them on thatching about 15 panels, which is about five square meters. for us, it took two people and five hours, and I trained the other person as I was building it. so it really comes down to planning the project out so you know exactly how many panels you need to cover. and then, the best panel size that I found is half meter by half meter. max you want to go is 0.8 meters, because otherwise the wind tends to tear it apart.

DB: and, I suppose these are more for residential use than commercial or public buildings?

KL: definitely more for residential use. but I also think you could use it in renovation projects, because of the supplementary insulation, where if you really needed insulation badly, and you couldn’t add enough inside the walls, you could add these externally, like on a roof or something.

DB: are there other uses for seaweed?

KL: yeah, you could use it to stock mattresses back in the day. and now in denmark, a lot of designers are using it to stuff furniture, which is really interesting. and I know some people also use it in duvets and yoga pillows. so there’s a lot of different applications that you can use with that and I’ve been also experimenting with using it as a fertilizer.

DB: the theme at design indaba this year is how design will change the future. can you explain a bit about your approach in relation to that?

KL: it’s not just my project but I feel also that my ideology as a young designer is so strongly rooted in ethics and returning to tradition, by, sort of, re-imagining it for future’s sake. especially with vernacular architecture is that historically, architects didn’t really engage with it because it was designed by the masses and not by architects, so peasants building their homes. I see this as really rich knowledge that we should try to re-learn and then apply and create architecture that’s really good for our environment, but also create architecture and treat our employees or co-workers really well and make sure they’re paid, even interns. and so that’s what I’ve been trying to do even in my small projects. that’s where I want the future to go. image courtesy of design indaba

image courtesy of design indaba

DB: what’s next for you?

KL: what’s next is I just renewed my grant. so I will be not only studying my pavilion, but trying to get plants to grow in my panels and create a small indoor wall installation with these growing panels. and, in addition to that, I’m also experimenting with new forms of algae and creating bio-plastics and leather out of seaweed. so I have a lot of different exciting options to go for right now. and it’s just finding time to explore them all.

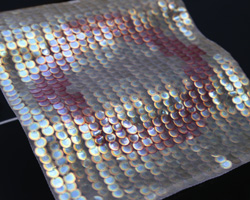

DB: and you’re showing something during milan design week this year as well, right?

KL: yes, it’s a very small installation with muDD architects. we’re trying to create something where you put your head in it, more like a model with the seaweed leather. it’s translucent and I’m making it with sliding panels so that you can slide the panels and increase the translucency or play with it as your head is inside this model.